The snake that can’t shed its skin is doomed to perish.

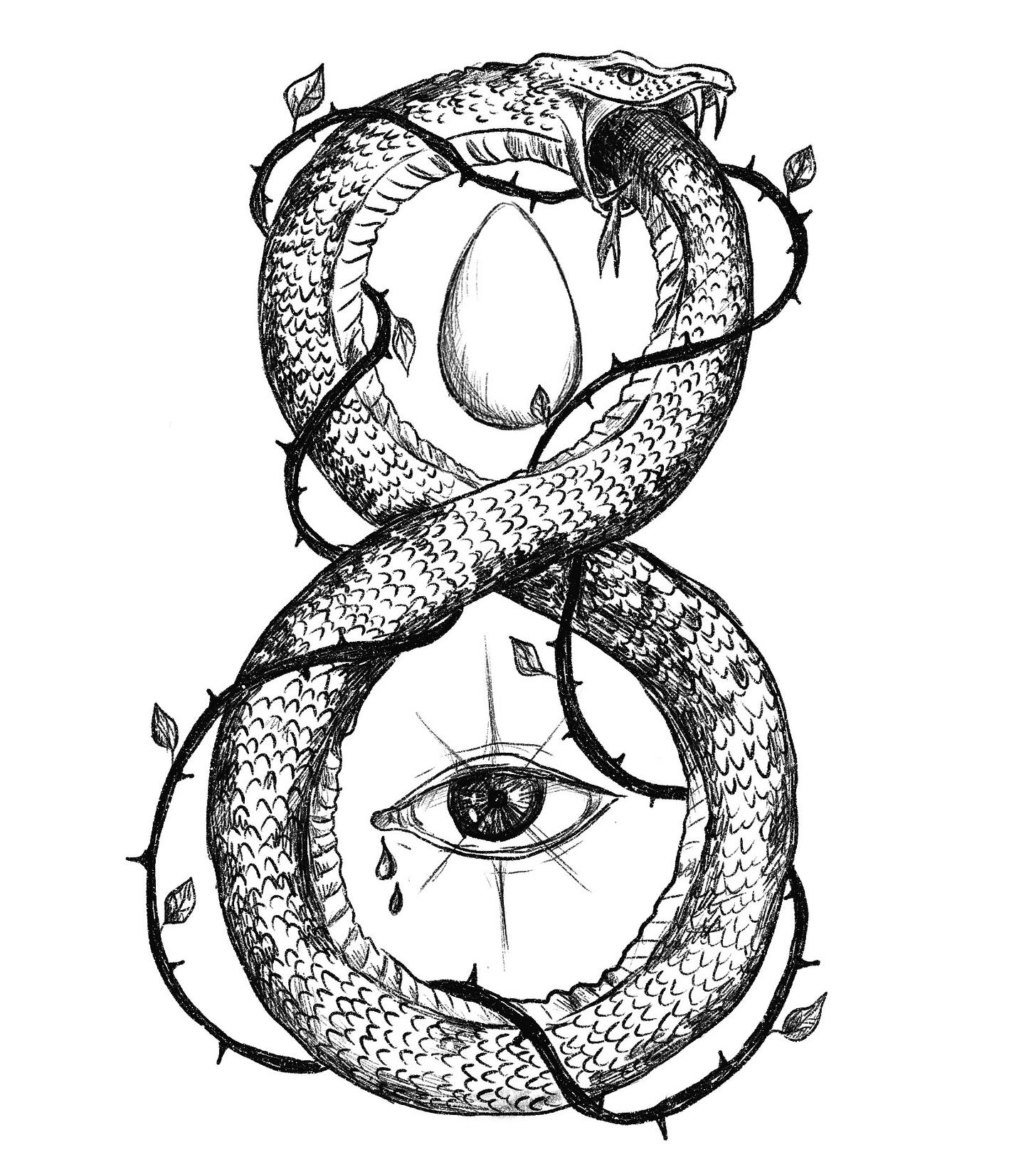

To me, this isn’t just a proverb—it is a lived truth. One of the pillars of my personal practice is animism. For the past five years, I have worked closely with the spirit of the Bear—its strength, protection, and ancestral wisdom a steady guide through times of embracing ancestral pain and becoming a mother. But in recent months, I’ve felt a shift. The Bear has begun to step back, and The Snake has emerged.

At first, I dismissed this shift as a coincidence—after all, it is the year of the Snake, and I was born in the year of the Snake. But the signs have continued to surface. I remembered vividly the day a snake crossed my path in the forest while I was pregnant. She stopped, turned her head to look at me, and I stood still, unthreatening. I took a picture of her and only later noticed: she, too, might’ve been carrying life? That moment, initially fleeting, now feels deeply significant—a mirror of the liminal space I was inhabiting then, between one life and another. The Snake seems to appear (physically or spiritually) in the moments when a change is needed.

More recently, I’ve felt an urge to cut my hair—a strange impulse for someone who has always treated her hair as a sacred connection to my land, I’ve never dyed or experimented with my hair. Since giving birth, I’ve watched it grow, a symbol of accumulated wisdom. But wisdom doesn’t come only from gentle moments. It is forged in experience, often through pain. This urge feels like a bell tolling, an inner call to make space for what’s next.

The snake has long symbolized the power of rebirth—the ability to shed the old self and emerge transformed. I have reached a point where I know: I will perish if I do not shed. So many elements of my life are coming to a halt. Something must give. Something must change.

To honor the beginning of this transformation, I offer this exploration of the snake's lore in Eastern Europe—not only as research or history, but as a personal invocation of what the serpent teaches: to leave behind what no longer serves, and to step into the unknown, raw and renewed.

In the vast terrain of Eastern Europe, where dense forests meet ancient steppe, the snake slithers not only through the soil but also through the stories, spells, and symbols that have endured for centuries. A creature feared and revered, the serpent occupies a liminal role in Slavic and Russian cultural memory: at once a harbinger of death, a vessel of prophecy, a symbol of divine protection, and a force of transformation.

The lore surrounding snakes in the Eastern European magical imagination is rich and contradictory. Tales from religious chronicles, practices of folk magic, and artifacts like zmeeviki amulets reveal a worldview in which the serpent is a figure that defies categorization. Transformation—whether of the body, the fate, or the soul—is at the heart of these narratives. Through the snake, people sought to change their fortunes, protect their lives, and even overcome death itself.

The Snake Beneath the Skull: Prophecy and Fate

In one of the earliest and most famous magical stories of Kievan Rus', the Tale of Bygone Years recounts a chilling tale from the year 912. A magician foretells that Prince Oleg will die because of his horse. Taking precautions, Oleg abandons the animal, only to mock the prophecy years later upon learning of the horse's death. But fate is not so easily outwitted: visiting the horse's remains, Oleg is bitten by a snake that emerges from its skull, and he dies shortly afterward.

This story is more than a simple moral about hubris. It reveals the snake as an agent of transformation, from life to death. The chronicler’s subsequent digression into biblical and early Christian magicians underscores the tension between condemning magic and recognizing its power. The snake, crawling forth from decay, becomes a vessel of prophecy fulfilled.

Tongues, Skins, and Talismans: Folk Magic and the Snake

In the world of folk practitioners known as kolduny, the serpent was a source of potent materials for transformation and defense. One spell involved killing a black snake, extracting its tongue, and sewing it into green and black taffeta to be worn in the left boot. When paired with garlic and a towel tied over the right breast, the charm was believed to protect its bearer in court or battle.

Snake parts were also used in household magic: snake-infused water healed fevers and marital discord, while the dried head of a serpent could be rubbed on the dead to bring them back to life, as in the bylina of Potuk Mikharla Lanovich. A snake hung on a birch tree summoned rain. These rituals point to the belief in the snake’s ability to mediate between worlds—to transmute illness into health, conflict into peace, and the inanimate into the animate.

In many Slavic regions, snakes were also associated with the ancestors. Killing a snake near the home was forbidden, as it could be a domovoi—a household spirit or the soul of a departed family member. Snakes appearing in dreams or visions were often interpreted as messages from the otherworld, guiding the dreamer through a transformation or rite of passage.

Zmeeviki: Amulets of Dual Faith and Dual Power

Perhaps the most iconic serpent artifact in Eastern European culture is the zmeevik (from zmiaja (Belarus),zmeya (Russia), zmiya (Ukraine)). These medallion amulets are marked by syncretism: one side bears Christian imagery (saints, angels, or the Virgin), while the other reveals pagan or magical motifs such as the Gorgon head with radiating snakes or a mounted warrior spearing a serpent.

Zmeeviki embodied transformation in a literal and symbolic sense. They were worn by commoners and elites alike, and even donated to monasteries. Some featured inscriptions like "Seal of God" or "One God, vanquisher of evil" alongside Greek or Church Slavonic prayers. Others carried the hystera motif, meant to ward off illness and she-demons such as Lilith or Antaura. In a world where spiritual safety required more than orthodoxy, the dual nature of zmeeviki allowed wearers to move between realms of belief, uniting Christian protection with ancient magical wisdom.

The Mounted Warrior and the Serpent: The Icon of Victory

The image of a mounted man piercing a serpent or dragon appears on seals and amulets from as early as the 10th century, long before it became officially associated with St. George. The figure likely evolved from representations of Solomon or other warrior saints such as St. Sisinnius, and served to ward off demonic illness and evil spirits.

In these depictions, the serpent or recumbent demon symbolized illness, infertility, or misfortune—forces to be transformed, conquered, and reabsorbed into a restored order. Over time, this iconography was absorbed into national symbolism: the rider became central to Muscovite seals, and eventually to the Russian coat of arms, where he remains today, spearing a dragon on the breastplate of the double-headed eagle.

The Alchemy of Belief: Amulets, Animals, and Magical Medicine

In addition to snakes, other animals played transformative roles in Slavic magic. Snake water, dried frogs, bat wings, and toad bones were part of healing and divination rites. Unicorn horns (likely narwhal tusks or mammoth ivory) were used as antidotes to poison and tools of royal power. These practices were not mere superstition—they represented a worldview in which nature itself held keys to change and protection.

In Slavic cosmology, the world was often imagined as resting upon or encircled by a cosmic serpent or dragon—a guardian of order and, when provoked, a bringer of chaos. This being served as a link between the upper world of the divine, the earthly realm, and the underworld. As such, the snake symbolized not only transformation but also the very structure of the cosmos.

Ivan the Terrible, who both practiced and persecuted magic, owned "unicorn" staffs and donated zmeeviki to monasteries. The paradox of a tsar who wielded magical symbols while punishing witches only highlights the deep cultural entrenchment of these practices. Transformation, in this sense, was not just individual but political: an assertion of divine right, mystical authority, and control over fate.

The Snake as Symbol of Shifting Worlds

In the lore and material culture of Eastern Europe, the serpent is never just a snake. It is a symbol of transition—between life and death, sickness and health, paganism and Christianity, nature and spirit. Whether buried under a birch tree, pressed into metal, or worn against the skin, the snake has long been a companion to those navigating change.

In embracing the snake, our ancestral traditions reveal an ancient belief in the power to transform one's reality. Through talisman, ritual, and myth, the serpent becomes a guide through the shadows, offering not only protection but the possibility of profound metamorphosis.

P.S. My toddler also wanted to add that some snakes only poop once a year.

Thanks! I was born in the Year of the Wood Snake. I tried to revision/rewrite the Medusa myth when young. My 1st Internet screen name was Medusafern, years later learning there is a fern of the same name. I have a snake tattoo over my heart. A homeopath once prescribed me Coral Snake remedy.

Recently, I'm having vivid experiences during meditation. In one, I asked a blue serpent in a blue night realm to quiet the chaotic chatter in my mind & grant me precision of focus. The snake met me eye-to-eye, & then a chest infusion resulted. What was that about? I'll appreciate learning from you.

I adore this so much! You’re a beautiful writer! I resonate with this as I have never in my life have I been connected to snakes and then August 2024 snakes started showing up in various ways in my life and then my twin sister bought me a snake ring and I had not even told her I was already connecting! And then I found out 2025 is the year of the snake. Really blew my mind!