Rusalka: The Evolving Myth of Slavic Water Spirits Pt.1

A deep dive into the origins, symbolism, and evolution of Slavic water spirits

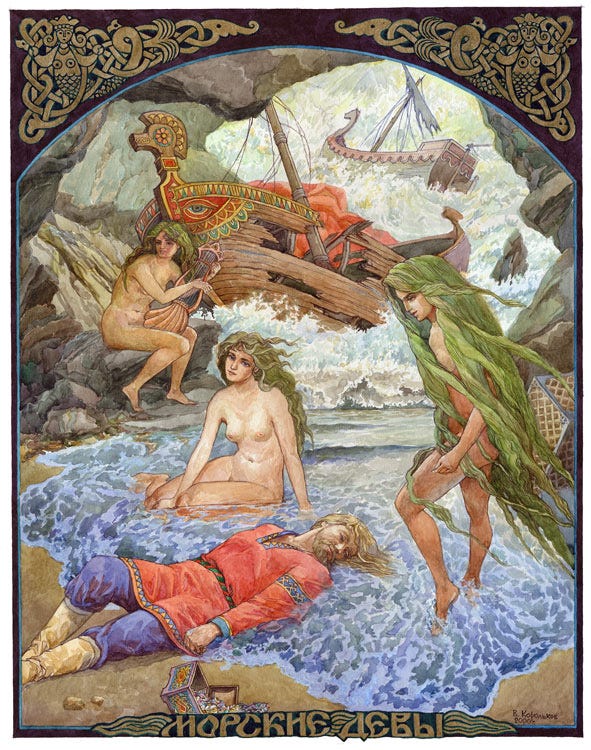

There’s so much to say about Rusalka and her insurmountable amount of lore. Is it an umbrella term for all types of watery spirits or is it specific to just the young women who passed away from unrequited love? It seems the jury is out on that one, or at least I got myself so wrapped up that I could find you proof for either of the theories.

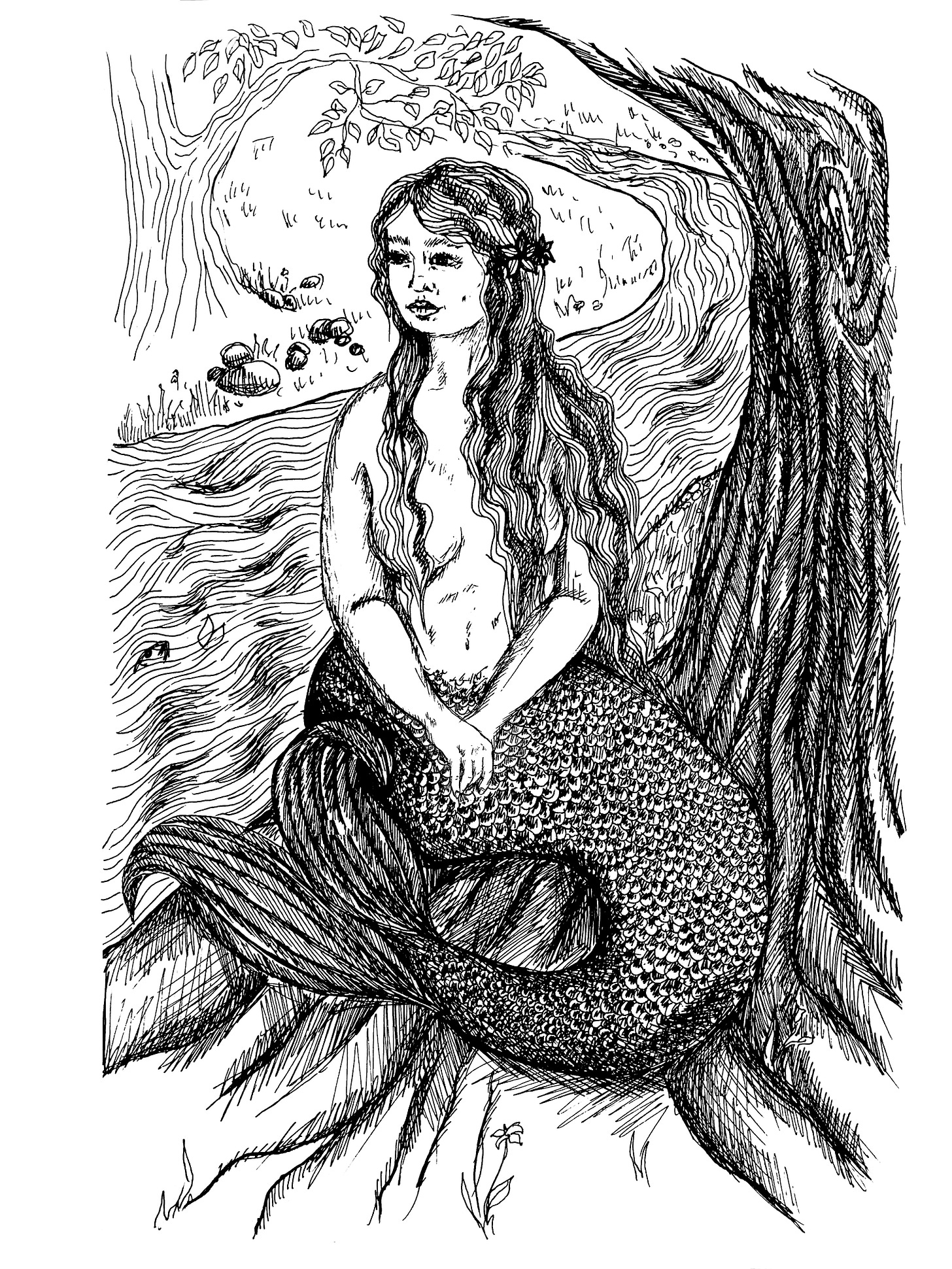

Rusalka is not quite like “the mermaid” the West is accustomed to, but to simplify things for readers, I may sometimes use the terms interchangeably.

This article aims to share more of the different types of water spirits I found throughout my years of obsessing with Rusalka and the general Mermaid archetype, rather than provide definite scientific research. Today, we’ll review some well-known and lesser-known Eastern European water spirits, and in the next article, we’ll dive deeper into even more information on them.

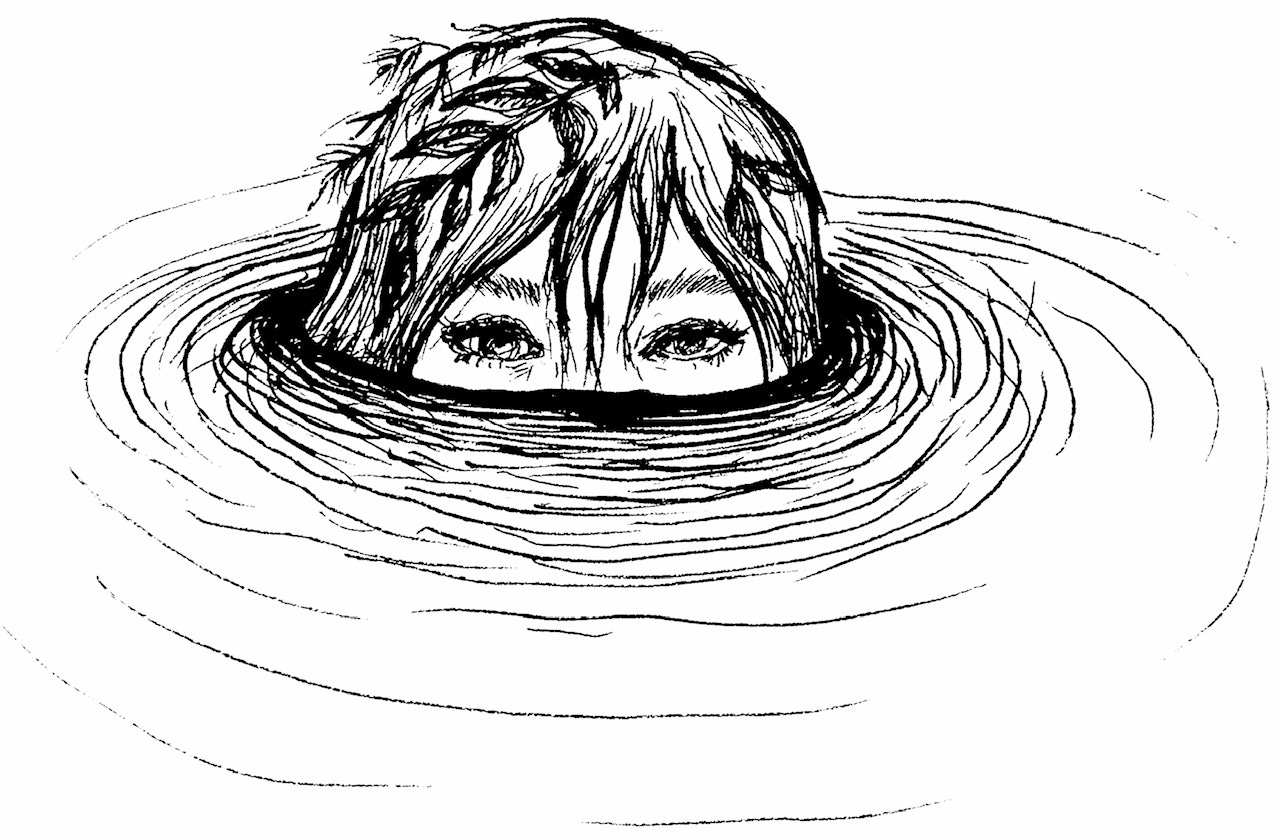

Rusalkas (Mermaids) have an enigmatic effect on people, holding our hearts and souls in suspense and wonder. Yet, surprisingly, they are quite low in the hierarchy of traditional Slavic mythology. Русалки (Rusalki) are seen as demons, ghosts, or spirits of tortured souls, without much divinity. However, the current image of a Рyсалка—a young woman void of love, seducing and killing men—is an invention of the 19th century. Before that, Rusalki were considered benevolent spirits; some were even considered deities. Let’s find out how these fantasies and perceptions of mermaids evolved in Slavic folklore.

The Origin of the Name

The origin of the name Рyсалка is still debated. Some suggest it comes from the word русый (rusyi), which means "light, white, or clean" in ancient Slavic languages. Others believe it comes from русaлия (rusaliya), derived from the Latin Rosalia, a term for Pentecost and the days surrounding it. Before the name Рyсалка became common, water spirits were known by various names, such as Чамка (Chamka), Шутовка (Shutovka), Водяница (Vodyanitsa), Купалка (Kupalka), Лоскотуха (Loskotukha), Хитка (Hitka), and many more.

Appearance and Habitats

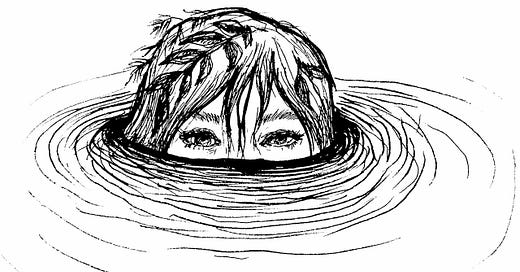

Unlike the Western concept of a mermaid with a fishtail, the Slavic Рyсалка had legs and looked like a regular woman. Rusalki lived in water but could also be found by creeks, lakes, swamps, trees, or even in fields. They were usually pale, with skin sometimes so transparent it was ghostly. Their hair could be black, green, or light русые (rusye), which refers to a blondish-brown shade, and they brushed it with a гребень (greben, or comb). These ethereal women were rarely seen during the day, as the depths of the night were their domain. Sometimes they would marry mortal men, but it never ended well, as the Рyсалка always returned to her natural habitat.

Becoming a Рyсалка

There are several ways one could become a Рyсалка (according to 18th-century folklore), but they were always women, often virgins who had died near water before their time. They could become Rusalki due to being unclean souls or suffering a violent death. The unclean souls included unbaptized babies, babies born out of wedlock who were drowned by their mothers, or suicide victims. Those who suffered violent deaths could have been murdered or betrayed by their lovers, leading to suicide.

After their death, they would haunt the body of water where they had died, lurking there until their deaths were avenged. Only then could they find rest. These unclean spirits typically had to spend a certain amount of time on Earth before being allowed to rest.

In pre-Christian times, Rusalki were seen as benevolent water spirits who helped nourish crops, making them highly respected in Slavic societies. They symbolized fertility, sexuality, fluidity, and femininity.

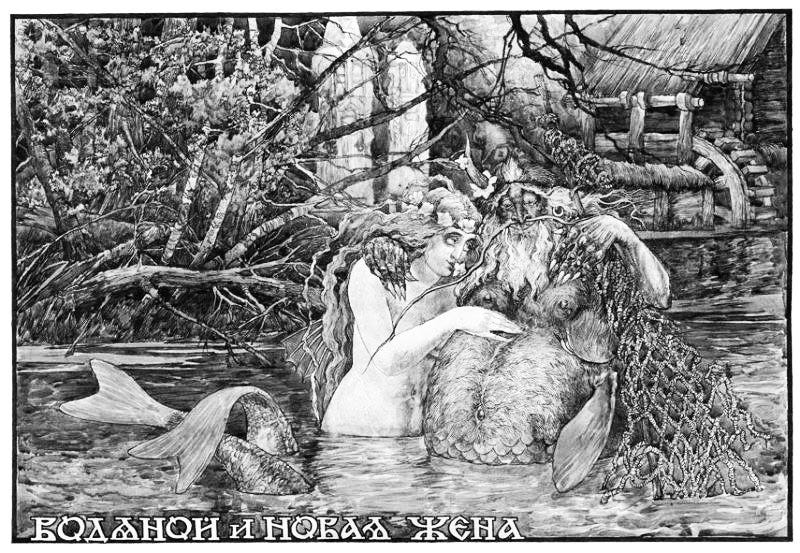

Водяной and Rusalki Hierarchy

In some regions, it was believed that the Водяной (Vodianoi), a male water spirit and trickster, ruled over all Rusalki. The Водяной had multiple wives, which adds a patriarchal touch to the myth. However, I prefer the interpretation from other regions where Rusalki are seen as independent spirits representing various aspects of nature rather than being subject to a male authority.

Variations of Рyсалки

Slavic folklore is rich with variations of the Рyсалка, and perceptions of these water spirits reflect the creativity and lifestyle of the people. This diversity can be both fascinating and confusing. I invite you to set aside judgment and simply enjoy the mysterious originality of our people. Let’s explore some known variations of Рyсалка.

Лоскотуха (Loskotukha)

The name Лоскотуха comes from the verb лоскотать (loskotat), meaning “to tickle.” This type of Рyсалка lured both men and women with her charms, only to tickle them to death. These mermaids were usually represented in the southern and southwestern regions of Russia. To protect themselves from the Лоскотуха, people would avoid going into forests alone during the period from Троица (Trinity) until Петров Пост (Peter's Fast), roughly from early May to late June. They would also avoid bodies of water, newly planted fields, and being outdoors after sunset.

If someone absolutely had to venture out during these times, they would carry a pouch of protective herbs like garlic or polyn’ (sagebrush, mugwort), and often wore a cross on their back (a post-Christianization practice) to prevent the Лоскотуха from sneaking up on them from behind.

Рyсалка Рось (Rusalka Ros’)

Legend has it that Рyсалка Рось was the divine source from which all other Rusalki came. This contradicts the idea that all Rusalki were tortured souls abandoned by men. Now, I’m cautious of the tale I’m about to relay, as I’m not 100% sure of its historical accuracy, yet it seems to be very popular.

Рyсалка Рось was the daughter of Дон (Don) and Асласа Святогорова (Aslasa Svyatogorovna), and her second father was Днепр (Dniepr). She had a son, Дажбог (Dajbog), with the god Перун (Perun), though their relationship was far from consensual. Perun, smitten by her beauty, tried to capture her, but her father Don created a storm to drown him. Perun transformed himself into a golden arrow and struck a rock near Рyсалка Рось, impregnating the rock with their son. Дажбог was later freed by Сварог (Svarog), the celestial blacksmith and Perun's father, thus becoming both Dajbog’s second father and grandfather.

Рyсалка Рось represents the personification of water, giving birth not only to mermaids but to all the people of Russia (smells like it could be a part of nationalistic mythology? stepping in to make this note, just in case). She controls the rain and creates the rainbow, which in some regions of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, was seen as a bridge between the gods and the people.

Чамка (Chamka)

I find Чамка fascinating because she feels like the most authentic representation of how Slavic people and Mordva viewed water spirits (this spirit probably was adopted by Slavic people from Mordva). The origins of Чамка are tied to the city of Ryazan and several Mordovian villages near Saransk. She is worshipped as a lake or river spirit, providing nourishment to crops and helping with fertility. Rituals to honor Чамка are still practiced in a few villages, where women dress in sheaves of green grass or shaggy clothing. The ritual, known as “the sending-off of Чамка,” is a playful parade in which a milkmaid (believed to be a conduit between gods and people due to her work with cows) plays the role of Чамка, symbolizing fertility. Below you can see some screenshots of the ritual, filmed by ethnographers for a documentary movie “Chamka”.

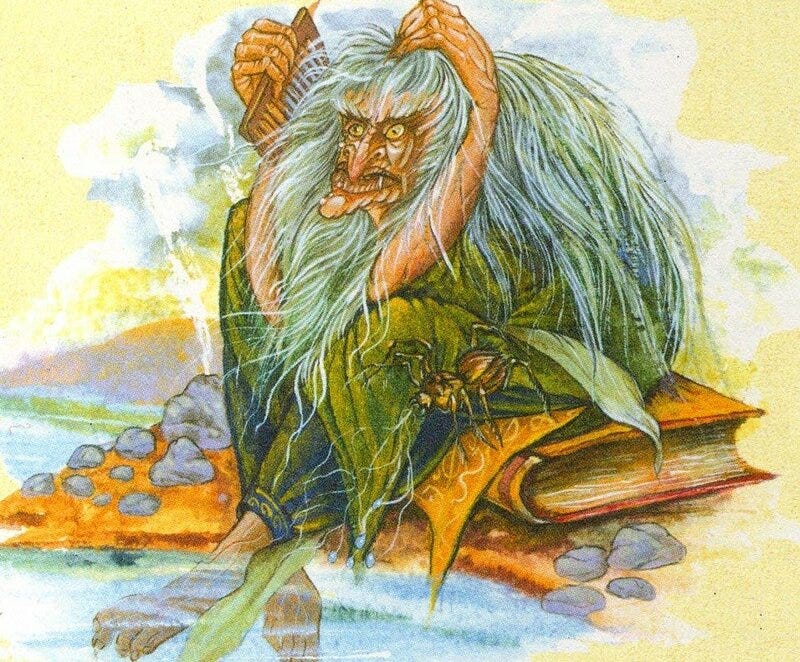

Лобасты (Lobasty)

The Лобасты are the only type of Рyсалка considered inherently evil. Some believe that regular Rusalki turned into Лобасты when people neglected to celebrate Рyсалка week. These creatures dwell in reeds by rivers and are often portrayed as old women resembling zombies. They are the most experienced and dangerous Rusalki, known for their deadly skills in tracking and killing humans.

Озерница (Ozernitsa), Болотница (Bolotnitsa), and Тречуха (Trechuha)

The names of these Rusalki are derived from their habitats. Озерница comes from озеро (ozero), meaning “lake,” and these spirits are found in the lakes of Belarus. They are not as attractive as their Ukrainian or Russian counterparts, often described with dirty green hair, bony bodies, and fins for feet. Болотница (Bolotnitsa), from болото (boloto, meaning “swamp”), is depicted as having frog legs hidden under lilypads and tries to seduce men to drown them in her swamp. Тречуха (Trechuha) lives in buckwheat fields, earning her name from гречка (grechka, meaning “buckwheat”).

Вила (Vila)

Вила (pl. Вили, Vily) are beautiful, eternally young water spirits similar to the nymphs of Greek mythology. They are shapeshifters and can transform into animals like horses, wolves, falcons, or swans. The cult of Вила was still practiced among South Slavs in the early 20th century, with offerings left in caves and near wells.

Мавка (Mavka) and Навка (Navka)

Мавка (Mavka) and Навка (Navka) are forest and water spirits found in Ukraine. The name Мавка comes from the ancient Slavic word мав (mav), meaning “dead one.” Мавка appears on full moon nights, fiercely protecting the natural world. She may ask passersby for a гребень (greben, or comb) to brush her curls—woe to anyone who refuses. Мавка is an exceedingly beautiful young woman, but her beauty is deceptive, as her back reveals green insides and a dead heart. Навка, on the other hand, is much darker and more malevolent, leaving sterility and death wherever she goes.

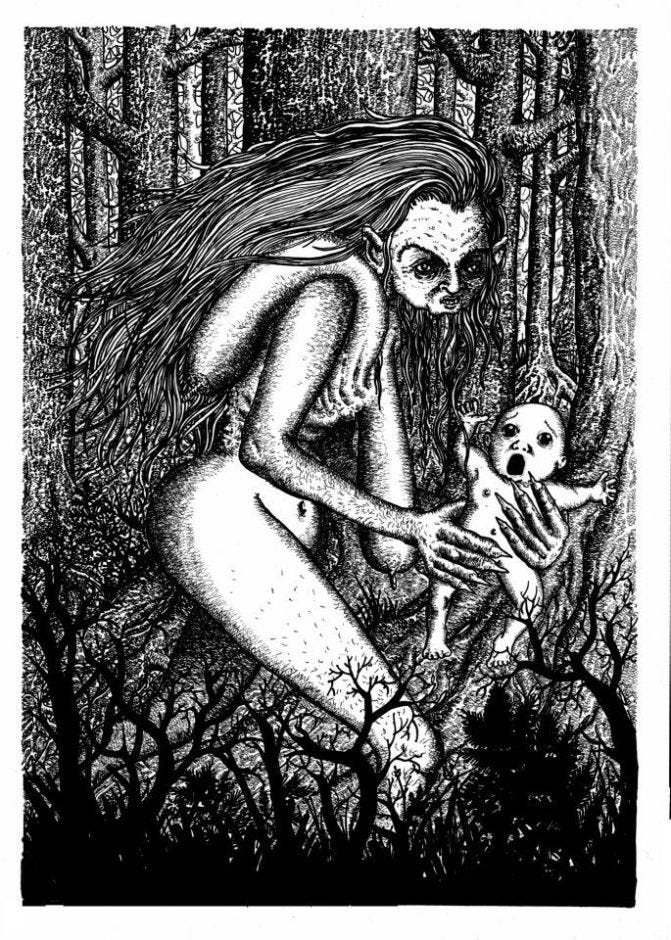

Богинка (Boginka)

Богинка (Boginka) or Дзивозона (Dziwozona) is a dangerous water spirit known to kidnap babies and replace them with changelings. She is associated with midwives, old maids, and unmarried mothers who died before childbirth. The name Дзивозона comes from див (div, meaning “god”) and жена (zhena, meaning “woman”), indicating her divine origins.