Kupala Night (June 21st for Poland, June 23rd for Ukraine, July 6th for Russia and Belarus) is one of those celebrations that has become a very popular “export” in our culture, partly due to its beautiful optics: young maidens in loose nightgowns gathering at night with candles, sending off their flower wreaths in the river in hopes of finding out about their future soulmates.

One of the most beautiful depictions of this night, in my opinion, has been created by Andrei Tarkovsky in his movie Andrei Rublev. Here are two clips that portray the ritual itself, and they have been occupying a massive amount of space in my brain for years since the first time I saw the movie, at times I feel like I try to hold people hostage just to share these visuals (thank you for being here voluntarily lol). Unfortunately, these are screen recordings with no sound, but you can watch the whole clip with sound on YouTube here, it will start right at this moment:

It’s hard to explain the sense of excitement, mixed with fear and simultaneously belonging, I feel when my mind gets lost in the torchlights of women running into the water. It’s raw, haunting, tactile, and visually hypnotising.

The following clip I’ve watched so many times that it is burned into my retina at this point (you can watch here with sound):

Now I could end this article here, drop my imaginary mic on behalf of Tarkovsky, and exit the premises. I genuinely don’t know if I govern my words as well as he conjures the fear and awe with his cinema. Alas, I shall continue.

Ivan Kupala is one celebration I’ve never participated in back home, and I deeply regret that. However, I'm also grateful that I was spared from getting involved with the nationalistic Rodnovery circles that practiced it most often back in the day. I say “back in the day” because there is currently a resurgence of this ritual in many Eastern European countries, and it’s now very popular, even among city dwellers; people gather for it in the same way people in the US gather for Coachella (only all ages are accepted and it’s free).

The Night of Ivan Kupala

The celebration of Ivan Kupala traces back to pre-Christian Slavic times, when the solstice marked a powerful turning point in the seasonal and spiritual calendar. Long before the name “Ivan”—a nod to John the Baptist—was appended to the festival, Kupala rites honored fertility, light, water, and fire. These rituals were tied to agricultural rhythms and cosmic balance. Kupala was the height of summer, when the sun stood still for a breath before beginning its slow descent, and the earth's body was at its most fertile. These were the days of ripening grain and swelling rivers, a sacred window when nature’s forces were not only visible but intensely felt.

Spiritually, Kupala Night is a liminal moment, a time when the veil between worlds grows thin and the unseen becomes tangible. It’s a night of thresholds: between fire and water, youth and adulthood, human and spirit, love and loss. Girls float flower wreaths to divine their romantic future. Boys seek the mythical fern flower, a symbol of inner illumination and forbidden knowledge. The bonfire becomes a living altar—offering protection, purification, and transformation. Water is both healing and dangerous, inviting participants to confront what lies beneath. These rituals were never purely symbolic. They were enacted with the deep understanding that nature’s forces could not just be honored but entered into a relationship with.

Practically, Kupala traditions were embedded in the land itself. The herbs woven into wreaths—mugwort, St. John's wort, yarrow, nettle—were not chosen at random but for their protective and healing properties. Jumping through the bonfire wasn’t just a game but a rite of passage, a test of courage and a spell of cleansing. Bathing in the river or rolling in the dew before sunrise was believed to grant health, fertility, and luck. Even the timing—held on the eve of July 6th into the 7th, aligned with the Julian calendar’s summer solstice period—was chosen with precision. These were not merely folk amusements, but carefully timed ceremonies tied to land, light, and the invisible currents of fate.

Today, many people are returning to Kupala with a new intention. In rural parts of Ukraine, Belarus, and Poland, it remains a community celebration. But across the Slavic diaspora, it is also being reclaimed as a personal ritual of belonging. A quiet wreath cast into a river. A solo fire lit in a backyard or on a beach. A whispered song or a barefoot dance under the moon. In this remembering, the celebration shifts—it becomes a way not only to honor ancestors but to step back into right relationship with the land, the body, and the rhythms of the earth that still pulse beneath the noise of modern life.

Rusalka Week and the Festival of Rusalii

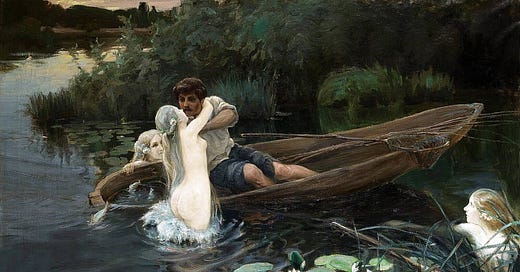

Rusalka Week, or Rusalnaya Nedelya or Zelyonïe Svyatki (Green Svyatki in opposition to Winter Svyatki), is a sacred and dangerous time in Slavic mythology, particularly in early June when the rusalki (water spirits) are believed to be at their most powerful. During this week, rusalki leave their watery homes to roam the earth, swinging from birch and willow trees, dancing in the moonlight, and interacting with humans in ways that can be both seductive and deadly. Swimming during Rusalka Week is strictly forbidden, as it’s said that anyone who enters the water during this time risks being dragged down and drowned by a rusalka.

The rusalki, in this context, are primarily spirits of young women who met untimely deaths, often by drowning, but also general ancestral spirits. They are tied to water and fertility and possess an ambivalent nature. While they are occasionally seen as protectors of crops and fertility, they are also feared for their malevolence and unpredictability, particularly during this week. Anyone who joins in the rusalki's nocturnal dances must dance until they collapse and die, consumed by the relentless, supernatural force of these spirits.

Rusalka Week traditionally takes place between June 10th and June 16th or June 20th to June 27th, depending on local customs. This period marks the peak of the rusalki’s activity when they are closest to the human world. While feared for their potential danger, rusalki are also honored and respected for their role in the fertility cycle of the land. It is during this week that peasants and farmers, particularly in agricultural communities, would seek to balance their relationship with these spirits—offering respect to ensure good harvests while protecting themselves from the rusalki’s more destructive tendencies.

The Festival of Rusalii

Rusalka Week is also intertwined with the Festival of Rusalii, an ancient Slavic fertility festival held in early May, approximately 18 days after the feast of Yarilo (the springtime fertility god). Traditionally, this festival aligns with the time when rye is blooming, and its rituals are tied to ensuring agricultural fertility. Initially, Rusalii began as a Roman festival of roses called Rosalia, but over time, it evolved into a Slavic festival dedicated to the rusalki and later became integrated into Christian traditions as part of Trinity Week.

During Rusalii, homes are decorated with green branches—often from linden, birch, and maple trees—and the floors are covered with fragrant herbs like wormwood and calamus to honor the spirits. Special care is taken not to offend the rusalki during this time, as they are known for their connection to weaving and washing. Therefore, sewing, washing linen, or weaving fences are considered forbidden tasks during Rusalii Week, as these activities could provoke the rusalki to cause misfortune, such as the loss of cattle or poultry.

The week is also marked by rituals intended to ward off weather damage and ensure a good harvest. Young people would circle the fields, carrying torches and adorning the land with green boughs as offerings to the rusalki. These boughs, often hung in barns or on the horns of cattle, symbolized a plea for the spirits’ protection and the fertility of the land. Another common practice involved burning herbs to fumigate livestock, driving away malevolent forces that might harm the animals.

Honoring the Dead During Rusalka Week

Many believe that rusalki are the spirits of ancestors, particularly those who died prematurely. Therefore, during Rusalka Week, rituals for the dead are an essential part of the festivities. Food and drink, especially pancakes and red eggs, are placed on the graves of the deceased, and libations of horilka (Ukr.), samogon (Rus.), or other spirits are poured over the graves to honor the dead and ask the rusalki to help the souls transition to peace.

These offerings serve to appease the rusalki as well. By honoring the spirits of the dead, the living sought to gain the rusalki’s favor, asking them to bless the crops and prevent storms or floods from destroying the harvest.

Banishing the Rusalki: The Ritual Conclusion of Rusalka Week

At the end of Rusalka Week, a ritual banishment or burial of the rusalka takes place. This practice is vital for ensuring that the rusalki return to their watery homes, leaving the human world for the remainder of the year. Such rituals were performed as recently as the 1930s in Russia and often took the form of community entertainment, though they were later banned by Soviet authorities.

The banishing of the rusalka also marks a crucial turning point in the agricultural cycle. By mid-June, peasants no longer desired more rain, as the crops had usually received sufficient water. What they needed was sunlight for their fields and hay to dry, ensuring winter food supplies for their livestock. Therefore, the symbolic act of sending the rusalka away represented a plea for drier, sunnier weather, which was necessary to complete the growing season successfully.

Despite this ritual farewell, the relationship with the rusalki remained essential throughout the agricultural year. While they were temporarily "banished," villagers knew they would need to call upon the rusalki again later in the summer or fall, as droughts could be just as dangerous as too much rain. Thus, maintaining a balanced, respectful relationship with the rusalki was crucial to ensuring the community’s survival and prosperity.

I love that you and this newsletter exist. 🥰 This was such a beautiful read and made me feel more connected to my ancestors and my past. I also love that there’s such a resurgence happening in the Slavic world, a return to the pagan and earth based traditions and wisdom that is deeply weaved into our DNA. It feels so good to witness.

Amazing stuff