Christmas Before the Tree

How Eastern Europe Went from Celebrating with Wheat to Christmas Trees.

You might think the Christmas tree has been around forever, but nope. For centuries, people here celebrated the season with symbols tied directly to the land they lived on. Wheat and Rye were essential—a literal golden thread connecting life, sustenance, and hope for the future. So, how did we go from wheat sheaves to evergreens? Buckle up; this story’s got tsars, revolutions, and a healthy dose of cultural nostalgia.

Wheat: The OG Christmas Decoration

Before anyone thought about dragging a tree indoors, wheat was the centerpiece of holiday decor. Why? Because wheat wasn’t just food; it was life. In harsh winters, when survival depended on last season’s harvest, wheat became a symbol of abundance and renewal. Families wove it into stars, spirals, and suns—all tied to cycles of nature and celestial hope. In Ukraine, the didukh (which means "grandfather spirit" or "the eldest") held court in homes, honoring ancestors and symbolizing prosperity. It wasn’t flashy, but it was deeply meaningful—the kind of thing that made you pause and feel connected to your community, your everyday struggles, and communal labor.

Enter the Christmas Tree (with a Side of Tsarist Drama)

Fast forward to the early 18th century, when Tsar Peter the Great was on a mission to make Russia more “Western.” Among his many reforms, he imported the idea of decorating with pine, fir, and juniper branches. It wasn’t a hit right away—people weren’t ready to swap out wheat for greenery—but the seed was planted (pun intended).

Thanks to German influences, Christmas trees started gaining traction in Russian high society by the 19th century. Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, Nicholas I’s German-born wife, brought her homeland’s traditions to Russia. Picture glittering trees with candles, sweets, and gilded apples at royal parties. The idea spread, and soon, even common folk were trying it.

The Soviet Era’s Plot Twist

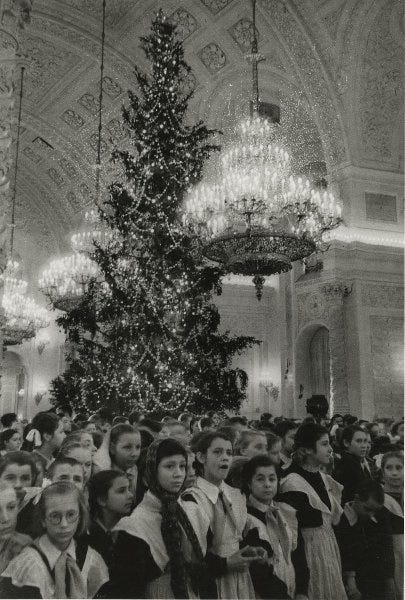

Then came the revolution—and with it, the banning of Christmas trees. The Soviets had zero time for anything tied to religion, so trees got the axe (figuratively and literally). But here’s where it gets interesting: in 1935, the government did a 180 and rebranded the Christmas tree as the New Year’s Yolka. Suddenly, trees were back, but now they had cosmonaut ornaments and industrial motifs.

The Wheat Comeback and Modern Mash-Up

Fast forward to today, and you’ll find both wheat and pine playing roles in Eastern European Christmas traditions. With a growing interest in reclaiming ancestral customs, wheat has made a bit of a comeback. Artists and crafters are creating gorgeous straw ornaments and reviving the didukh tradition. It’s not just about nostalgia; it’s about reconnecting with the earth and honoring where we came from.

This serves as a reminder that traditions are living, breathing things. Whether it’s a wheat sheaf or a decked-out pine tree, what really matters is the meaning we attach to it. Decorating for Christmas (or New Year’s, or Solstice—you do you) is about grounding yourself in something bigger than the daily grind. So, next time you’re hanging ornaments, maybe throw in a little wheat. After all, traditions aren’t about what’s trendy; they’re about what speaks to your heart.